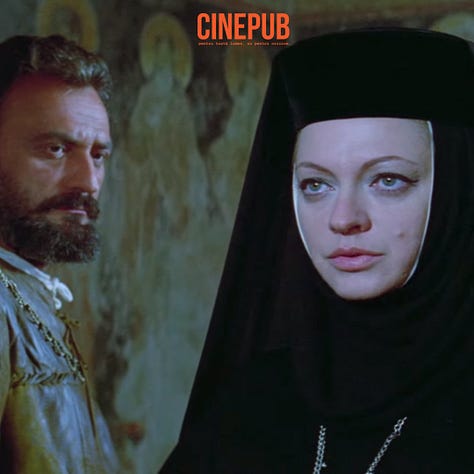

Michael the Brave (1970): Broken, Myth-Making Bones (1/2)

Michael feels both like a boys' play with weapons, horses, and pyrotechnics, and a strenuous myth-making narrative curating the dignified heritage of Romanians.

Known as a fundamental tool in the arsenal of film theorists, the famous observation by J.L. Godard (refined by Jacques Rivette) that any fictional film is in itself a documentary of its own making is undoubtedly not only applicable to the mammoth that is Michael the Brave (1970), but also perhaps one of the most rewarding keys to interpreting the viewing of this celebrated biopic directed by Sergiu Nicolaescu.

This perspective is supported by the filmmaker himself in a debate organized by Cinema magazine in June 1974, where Nicolaescu states that these types of films (historical ones) "represent the moment when they were made and strongly support the idea that they are a social demand of the present.”

Packed into almost three and a half hours, divided into two parts: Călugăreni and Unirea, featuring a strong presence from the Romanian Socialist Republic's army through foot-soldiers, this first part of Michael the Brave glides above the Romanian ruler’s battlefields, passing from one fight to another, depicting the carnage as a series of historical events that converge — alongside strategic maneuvers and political alliances, both domestically and internationally — towards the decisive battle of Călugăreni.

Careful to portray the sacrifice made by the soldiers of Wallachia, attentive to the nuances of Mihai Pătrașcu’s (the ruler’s real name) heroism — especially in the context of him coming from a high family background, i.e., not being a commoner — Michael feels both like a boys' play with weapons, horses, and pyrotechnics, and a strenuous myth-making narrative curating the dignified heritage of Romanians, from their origins to the socialist present. Because, as noted by Bogdan Jitea in Cinema in the Romanian Socialist Republic, "the (Romanian socialist) regime directly connected to the legitimizing vein of the Past in order to overcome the deficit of trust in the solutions offered by communist ideology.”

Beyond their creative intention of mythologizing, the films in the series of Cinematic National Epics, of which Michael the Brave is a part, alongside Tudor (1963, dir. Lucian Bratu), The Dacians (1967, dir. Sergiu Nicolaescu), The Column (1968, dir. Mircea Drăgan), and others, also give rise to the phenomenon, as widespread as it is fleeting in collective memory, of stuntmen.

The tectonic moving images with the crowds of armored bodies wielding swords demand others images. Those of endless pauses between setting up shots. The scorching sun. The sluggishness of "war," felt more authentically in anticipation than in attack. Repeated falls and dust in the eyes. All of this can be read in the astonishing diary-novel of Aurel Grușevschi, "From the World of a Stunt Performer," which makes use precisely of the inglorious life of the stuntmen behind the armor.

What's remarkable about Grușevschi is that through his writings, he offers unmediated access to the flicker of consciousness of the person who willingly leaps from a horse, who passes through windshields and flames alike; a true cognitive Blitzkrieg rendered without literary preciousness, but with the resilience of those who put back their own dislocated shoulders like it’s no biggie.

(Emil Vasilache, cinepub.ro)